During Grand Morning Report, we briefly discussed a patient

with sickle cell disease and a history of acute chest syndrome. This is a common complication of sickle cell disease and is a frequent cause

of death in this patient population, making early diagnosis and treatment critical.

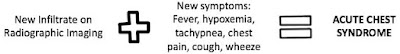

What is acute chest

syndrome?

What causes acute

chest syndrome?

A number of different causes for acute chest syndrome have been

identified. These include the following:

- Pulmonary infarction due to vaso-occlusion from sickled cells

- Fat embolism due to release of fat into the bloodstream from bone marrow infarction during a vaso-occlusive crisis

- Infection

- Hypoventilation

It is also important to recognize that patients can present

with what appears to be a straightforward pain crisis and still go on to

develop acute chest syndrome during their hospitalization.

What else should be

on the differential?

Given that many of the features of acute chest syndrome are

vague or non-specific, other etiologies for the patient’s presentation should

be considered and/or ruled out. The

following are alternate diagnoses not to miss:

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Pulmonary embolism

- Exacerbation of asthma or COPD

- Pneumonia (although this is often indistinguishable from acute chest syndrome)

How is acute chest

syndrome treated?

The mainstays of treatment for a vaso-occlusive crisis still

apply:

- Early and aggressive pain control

- IV fluids to maintain normovolemia

- Oxygen

- Incentive spirometry

- DVT prophylaxis

However, the following therapies should also be considered, along with Hematology consultation:

Antibiotics:

- Since it is often impossible to distinguish pneumonia from acute chest syndrome, patients should be started on antibiotic therapy early. This should also include coverage for atypical organisms as mycoplasma pneumoniae and chlamydia spp. are thought to be frequent culprit organisms.

·

Simple vs. Exchange Transfusion:

- Simple transfusion should be considered for mild acute chest syndrome while patients with moderate to severe disease typically require exchange transfusion. The goal of both therapies is to lower the overall proportion of hemoglobin S and improve oxygenation.

References and more reading...

Paul RN, et

al. “Acute chest syndrome: sickle cell

disease”. Eur J Haematol. 2011 Sep;87(3):191-207.

Vichinsky EP, et al.

“Causes and outcomes of the acute chest syndrome in sickle cell

disease. National Acute Chest Syndrome

Group”. NEJM; 2000 Jun

22;342(25):1855-65.